A 22-year-old from Dumas, Arkansas would cross the unbreakable barrier at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City…

The target for any aspiring men’s 100m sprinter is to run the distance in under 10 seconds. Running a sub-10 second time can immediately elevate a sprinter into the spotlight, putting them among the very best 100m runners in the world. Those who consistently break the 10-second barrier are considered truly world-class and are often the athletes who walk away from the major championships with medals around their necks.

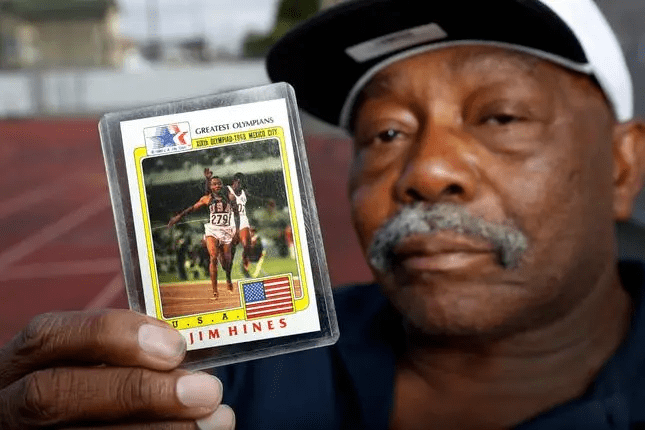

At the time of writing, a total of 156 sprinters from 28 countries have recorded sub-10-second times in the men’s 100m. However, only one man can claim to be the first. That man is American sprinter Jim Hines, who achieved the feat in the 100m final at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. The following article will tell the story of Jim Hines, that 100m final and how Hines’ unique claim to fame would not be fully ratified until nearly a decade after the original race had already been run.

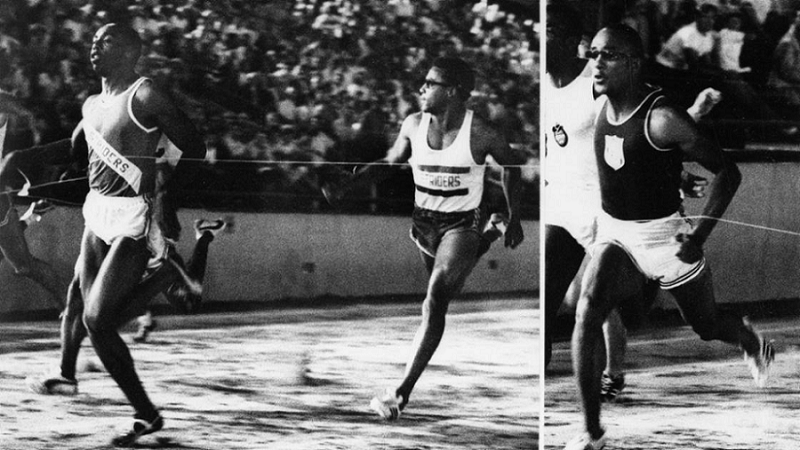

The ‘Night of Speed’

Heading into the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, a Games that would later be remembered for many different reasons, 22-year-old sprinter Jim Hines was among those considered as a strong gold medal contender in the 100m. Born on 10th September 1946 in Dumas, Arkansas, as the ninth of twelve children, Hines and his family would later move to Oakland, California, where Hines would attend McClymonds High School. During his time at McClymonds, Jim Hines would take up track and field. Before graduating in 1964, he would show his promise, running the 220 yards (201 metres) in 21.54 seconds and the 100-yard dash (91m) in 9.84 seconds. He would graduate from McClymonds as one of the best high school athletes in the country.

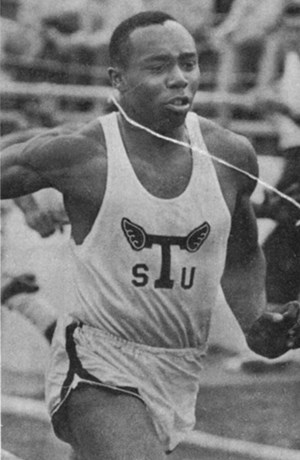

Choosing to enrol in Texas Southern University and joining the athletics squad coached by 1956 triple Olympic sprint (100m, 200m, 4x100m relay) gold medallist Bobby Morrow, Hines would quickly become one of the best sprinters in America. At 19 years old, he would earn a silver medal in the 220-yard dash at the 1965 US National Championships. The following year, he would win gold in the 220 yards and claim silver in the 100 yards behind Charlie Greene, who would quickly become his biggest rival in the event. Finally, in 1967, Jim Hines would win the 100-yard dash ahead of Greene, while a championship record time was required for Tommie Smith to beat Hines to gold in the 220-yards. Therefore, heading into 1968, Jim Hines had an excellent chance of bringing home gold from the Olympics in Mexico City, be it 100m or 200m.

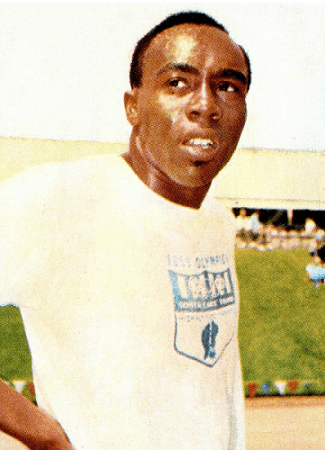

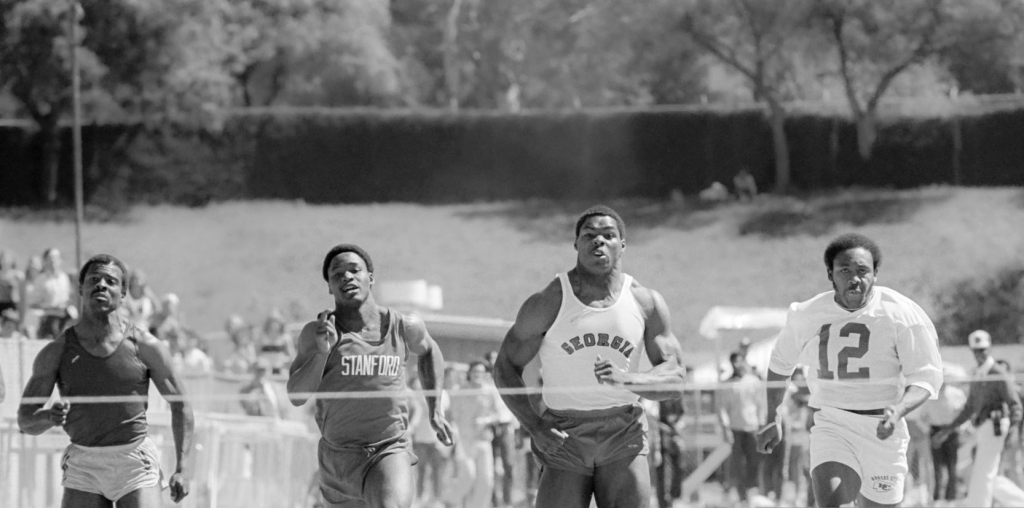

Hines would travel across the border into Mexico as one of the fastest 100m runners in the world on form, having broken the world record earlier in the year. In June 1968, he had finished 2nd in the 100m final at the US National Championships behind Charlie Greene, failing to defend the title in Sacramento that he had won in Bakersfield the previous year. However, his actions in the semi-finals of the same event would mean that he came away from those national championships as one of the three fastest men in the world. In his semi-final, Jim Hines would finish 1st in a time of 9.9 seconds. Ronnie Ray Smith, who finished 2nd, would also run a time of 9.9 seconds. To complete a brilliant trifecta, Charlie Greene (the eventual winner of the event) would win the second 100m semi-final in 9.9 seconds.

As all three men had run under 10.0 seconds (the official 100m world record currently held by eight men including Jim Hines) in their respective semi-finals, Hines, Smith and Greene were all recognised as having run a new world record time of 9.9 seconds. The unbelievable achievement of the three American athletes inside the Hughes Stadium in Sacramento, California, on 20th June 1968, would lead to this day later being referred to as the ‘Night of Speed’.

If you are wondering why I began this article by speaking about Jim Hines breaking the 10-second barrier for the first time at the 1968 Olympic Games, when he had already achieved the honour four months earlier at the US National Championships, all will soon be explained.

In 1977, fully automatic timing was accepted as the primary way of timing athletics events. Before this year, official race times could come from automated timing devices or ‘hand timing’, which calculated race results using three stopwatches controlled by timekeepers. The computerised machines began when the starting gun sounded, while ‘hand timing’ would start as soon as the timekeepers reacted to the starting gun and started the stopwatches. At the time, stopwatches could only record race times to one decimal place, hence the times of Hines, Smith and Greene being recorded as 9.9 seconds. By comparison, automated timing devices could record times up to hundredths of a second, leading to more accurate race times being recorded.

Why do I mention all of this? The 1968 US National Championships in Sacramento would primarily utilise ‘hand timing’, and those times recorded by stopwatches would be classed as the official times. However, these championships would also use an experimental automatic timing machine made by Accutrack. While the men with the stopwatches would all register Jim Hines, Ronnie Ray Smith and Charlie Greene as having broken the 10-second barrier by running 9.9 seconds each, the Accutrack automatic timing machine would say otherwise. According to this machine, Hines had run the fastest of the three, posting a time of 10.03 seconds to win the first 100m semi-final, with second-placed Smith finishing eleven-hundredths of a second behind in 10.14 seconds. Meanwhile, Charlie Greene would record an ‘automatic’ time of 10.10 seconds to win the second semi-final.

Therefore, despite what the stopwatches read, the more accurate timing method would show that the 10-second barrier was still fully intact. However, Hines, Smith, and Greene would all head south of the border for the 1968 Olympic Games, hoping to come away with 100m gold while believing that they had all ran under 10 seconds and were, therefore, the world record holder.

1968 Olympic Games

After their performances in Sacramento, Jim Hines, Charlie Greene and Ronnie Ray Smith would all travel to Mexico City as part of the 1968 USA Olympics Track and Field squad. After finishing 1st and 2nd respectively at the National Championships, Greene and Hines would compete in the individual men’s 100m along with Mel Pender. Pender had reached the 100m final at the previous Olympics in Tokyo, finishing 6th and therefore had major competition experience which the other two lacked. Ronnie Ray Smith, who had finished joint-3rd in the final behind Greene and Hines, would join his fellow world record holders in the 4x100m relay team. Along with the USA athletes, other potential gold medal candidates in the men’s 100m included Roger Bambuck of France, Pablo Montes of Cuba, former world record holders Enrique Figuerola (Cuba) and Harry Jerome (Canada), and Jamaican runner Lennox Miller. If these men were to achieve their dream of becoming an Olympic gold medallist, they would have to race four times in two days. They would need to progress through three preliminary rounds to reach the final before running as fast as they could against the very best in the world to earn a medal.

Jim Hines would begin his debut Olympic Games in the second of nine first-round heats on 13th October 1968. The 22-year-old would easily win his heat in 10.26, with Madagascar’s Jean-Louis Ravelomanantsoa (10.30), Côte d’Ivoire’s Gaoussou Koné (10.37) and Uganda’s Amos Omolo (10.50) also qualifying for the next round behind the young American. Hines’ time of 10.26 would see him qualify sixth-fastest for the quarter-finals. His close rival Charlie Greene would record the fastest time of 10.08 in winning Heat One. Fellow heat winners Pablo Montes (10.14), Lennox Miller (10.15), Roger Bambuck (10.18) and Heat One runner-up Hideo Iijima (10.24) would also run faster than Jim Hines in this first stage. However, as a heat winner, Hines would earn himself a favourable draw in the quarter-finals.

1968 Olympics Men’s 100m Heat 2 Result

| Position | Athlete | Country | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Jim Hines | United States | 10.26 Q |

| 2nd | Jean-Louis Ravelomanantsoa | Madagascar | 10.30 Q |

| 3rd | Gaoussou Koné | Ivory Coast | 10.37 Q |

| 4th | Amos Omolo | Uganda | 10.50 q |

| 5th | Porfirio Veras | Dominican Republic | 10.51 |

| 6th | Julius Sang | Kenya | 10.64 |

| 7th | Jorge Vizcarrondo | Puerto Rico | 10.71 |

| 8th | Manuel Planchart | Ecuador | 10.80 |

Later on 13th October, Jim Hines would return to the track inside the Estadio Olímpico Universitario in the first of four quarter-finals. In his quarter-final, Hines would line up alongside fellow heat winners Lennox Miller and Enrique Figuerola and runners-up Iván Moreno, Karl-Peter Schmidtke, Ron Jones and Andrés Calonge and fastest loser Vladislav Sapeya. In the end, the three heat winners would all end up achieving automatic qualification for the Olympic semi-finals, with just 0.12 seconds separating the three men. Jamaican sprinter Miller would win in 10.11, three-hundredths of a second ahead of Jim Hines in 2nd (10.14) and nine hundredths ahead of Enrique Figuerola in 3rd (10.23). Iván Moreno would complete the qualifiers, finishing 4th in a time of 10.37 seconds. The times of Miller and Hines would see them qualify 3rd and 4th-fastest for the semi-finals. Charlie Greene would once again top the timesheets, with the US national champion underlining his gold medal potential with a time of 10.02. Cuban athlete Hermes Ramírez would also impress, winning quarter-final two in 10.10.

1968 Olympics Men’s 100m Quarter-Final 1

| Position | Athlete | Country | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Lennox Miller | Jamaica | 10.11 Q |

| 2nd | Jim Hines | United States | 10.14 Q |

| 3rd | Enrique Figuerola | Cuba | 10.23 Q |

| 4th | Iván Moreno | Chile | 10.37 Q |

| 5th | Andrés Calonge | Argentina | 10.39 |

| 6th | Ron Jones | Great Britain | 10.42 |

| 7th | Karl-Peter Schmidtke | West Germany | 10.48 |

| 8th | Vladislav Sapeya | Soviet Union | 10.51 |

After finishing 2nd in his quarter-final, Jim Hines would find himself in the more difficult of the two Olympic semi-finals. The threats facing Hines in semi-final 1 were reigning Olympic 100m silver and bronze medallists Enrique Figuerola and Harry Jerome and European silver medallist Roger Bambuck. All these men had recent personal bests of 10.0 seconds. Other threats would also come from quarter-final two winner Hermes Ramírez and American teammate Mel Pender, who was known for his fast start. Filling out the starting list for this first semi-final were Harald Eggers of East Germany and Hideo Iijima of Japan. The first four across the line would qualify for the 1968 Olympic men’s 100m final.

Faced with all this competition, Jim Hines would win the first 100m semi-final in 10.08, 0.05 seconds slower than the ‘world record’ time he ran in the semi-finals of the US National Championships (10.03). Roger Bambuck would finish second in 10.11, Harry Jerome would reach his second consecutive Olympic 100m final in 10.17, and Mel Pender would ensure a second American athlete made the final by running 10.21. Just 13 hundredths of a second would separate the four automatic qualifiers from this first semi-final.

Hines’ time of 10.08 would mean that he qualified fastest for the Olympic 100m final. Bambuck would qualify second (10.11), followed by Charlie Greene, who would win semi-final two in 10.13. Harry Jerome (10.17) was fourth-fastest ahead of second semi-final runner-up Pablo Montes (10.19). Finally, Mel Pender (10.21) would make it three American athletes in the 100m final and Jean-Louis Ravelomanantsoa of Madagascar would complete the field (10.26) by adding an African presence to proceedings.

| Position | Athlete | Country | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Jim Hines | United States | 10.08 Q |

| 2nd | Roger Bambuck | France | 10.11 Q |

| 3rd | Harry Jerome | Canada | 10.17 Q |

| 4th | Mel Pender | United States | 10.21 Q |

| 5th | Enrique Figuerola | Cuba | 10.23 |

| 6th | Hermes Ramírez | Cuba | 10.25 |

| 7th | Harald Eggers | East Germany | 10.29 |

| 8th | Hideo Iijima | Japan | 10.34 |

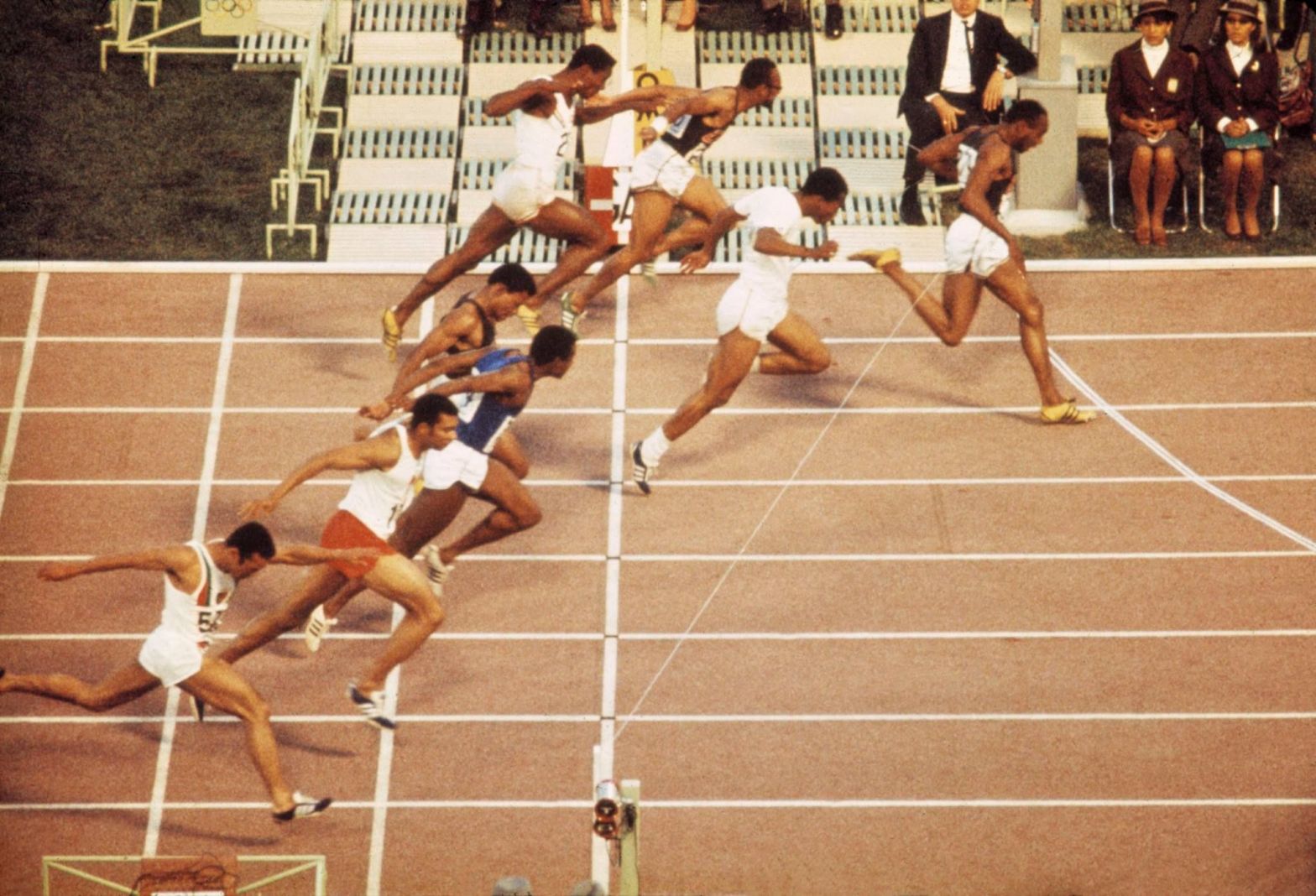

A total of 0.18 seconds would separate the qualifying times of the eight men who walked onto the track of Mexico City’s Estadio Olímpico Universitario for the Olympic men’s 100m final on the evening of 14th October 1968. The field would feature three athletes representing the USA, all hoping to add their names to the list of American men who had previously won this prestigious event. Before this final, a US runner had claimed the gold medal in 11 out of 15 Olympic 100m finals. Jim Hines, Charlie Greene and Mel Pender would hope to continue that impressive record by winning this race. Hines and Greene would also enter the race as the joint-world record holder, and equalling that record or even setting a new mark would cap a fantastic performance for either man.

As well as Hines and Greene, the race featured former world record holder Harry Jerome. Jerome hoped to convert his bronze medal from Tokyo 1964 into gold in Mexico City, becoming the second Canadian to win the 100m after Percy Williams at Amsterdam 1928. Similarly, Roger Bambuck could become the fourth European to win the race after British pair Reggie Walker (1908) and Harold Abrahams (1924) and East German Armin Hary (1960), while becoming the first to do it for France. In addition, Jamaica’s Lennox Miller and Cuba’s Pablo Montes could become the first Olympic 100m champions from the Caribbean (and the first American winners outside of North America), and Madagascar’s Jean-Louis Ravelomanantsoa could become the event’s first African winner.

In the final, Jim Hines would start in lane three, between Pablo Montes (lane two) and Lennox Miller (lane four). Hines’ American teammates Charlie Greene and Mel Pender would flank Montes and Miller in lanes one and five, respectively, while Roger Bambuck (six), Harry Jerome (seven) and Jean-Louis Ravelomanantsoa (eight) would take up the outside lanes.

1968 Olympics Men’s 100m Final Start List

| Lane | Athlete | Country | Qualifying Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Charlie Greene | United States | 10.13 (3rd) |

| 2 | Pablo Montes | Cuba | 10.19 (6th) |

| 3 | Jim Hines | United States | 10.08 (1st) |

| 4 | Lennox Miller | Jamaica | 10.15 (4th) |

| 5 | Mel Pender | United States | 10.21 (7th) |

| 6 | Roger Bambuck | France | 10.11 (2nd) |

| 7 | Harry Jerome | Canada | 10.17 (5th) |

| 8 | Jean-Louis Ravelomanantsoa | Madagascar | 10.26 (8th) |

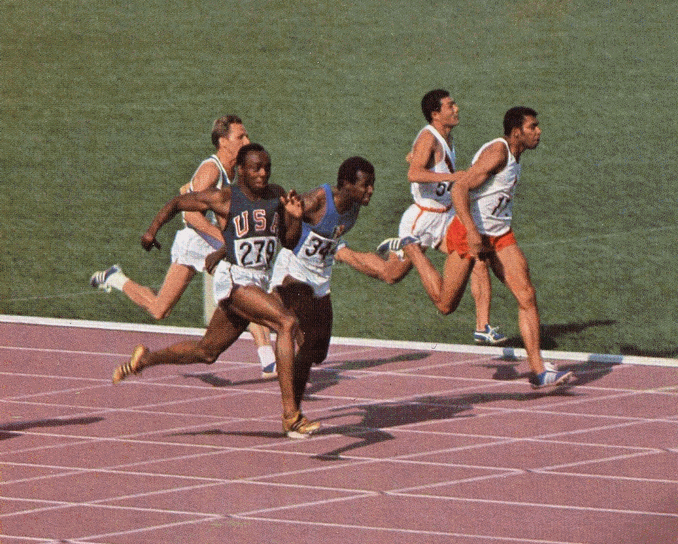

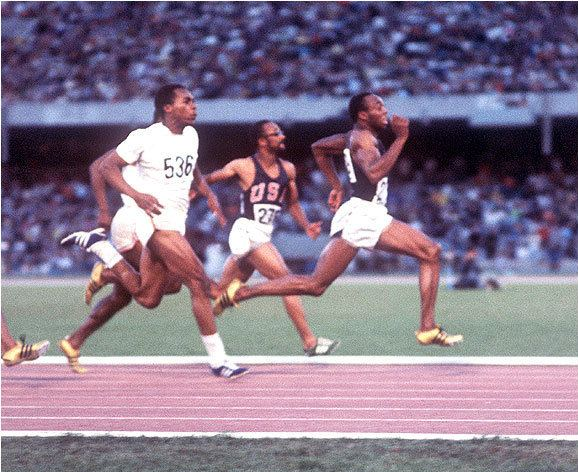

Mel Pender would react quickest to the starting pistol and lead at 30m with his American compatriots Charlie Greene and Jim Hines closest behind in 2nd and 3rd. However, Pender’s early lead would quickly evaporate as Greene, Hines and Lennox Miller had all passed the diminutive American by the halfway point. At this point, Charlie Greene had an inch lead over Jim Hines with Lennox Miller close behind. Pender was in 4th place and going backwards as Pablo Montes in lane 2 drew level with him. Even at this stage, the outside lanes of Bambuck, Jerome and Ravelomanantsoa were non-factors in regards to the medals.

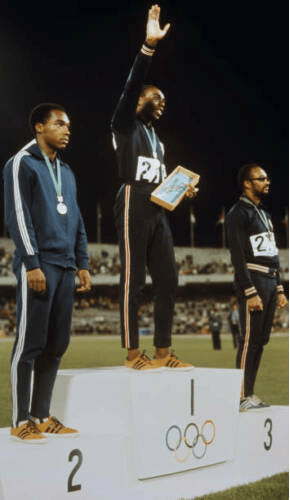

With 30m to go, Charlie Greene was still leading from Jim Hines, with Pablo Montes in 3rd and Lennox Miller in 4th. Ten metres later, Hines would overtake his fellow world record holder and run away from the field while Lennox Miller would pass Pablo Montes to move into the bronze medal position. The 22-year-old Jamaican would pass the fading Greene five metres from the finish line but could not catch Jim Hines. The 22-year-old from Arkansas would cross the line two metres ahead of Miller to win the Olympic gold medal, with the Jamaican claiming silver and Charlie Greene getting the bronze.

As Jim Hines crossed the finishing line, the timekeeper’s stopwatches would stop at 9.9 seconds. According to this system, Hines had equalled his world record run from the US National Championship, becoming the first man to twice break the 10-second barrier. However, while the ‘hand’ timers suggested that Hines had equalled the current world record, the automatic timers read differently. The automatic timer would first read 9.89, a new world record. This would quickly be rounded down to 9.95 seconds.

You may remember that the automatic timers had calculated the 9.9 world record runs of Hines, Charlie Greene, and Ronnie Ray Smith set at the US National Championships as actually having been run in times of 10.03, 10.10 and 10.14 seconds, respectively. Considering these facts, the time Hines had run to win the Olympic final was actually the first time anyone had broken the 10-second barrier for the men’s 100m. Therefore, instead of sharing the honour of breaking 10 seconds with Greene and Smith, Jim Hines was, in fact, alone in achieving this incredible feat. However, considering that hand-timed runs were used for official race results until 1977, the truth of Hines’ achievement would not come to fruition for another decade. Instead, he would win the Olympic gold medal while running 9.9 seconds for the second time in his career and equalling his own world record.

1968 Olympics Men’s 100m Final Result

| Position | Athlete | Country | Time (hand) | Time (automatic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Jim Hines | United States | 9.9 (=WR) | 9.95 ( new WR) |

| 2nd | Lennox Miller | Jamaica | 10.0 | 10.04 |

| 3rd | Charlie Greene | United States | 10.0 | 10.07 |

| 4th | Pablo Montes | Cuba | 10.1 | 10.14 |

| 5th | Roger Bambuck | France | 10.1 | 10.14 |

| 6th | Mel Pender | United States | 10.1 | 10.17 |

| 7th | Harry Jerome | Canada | 10.2 | 10.20 |

| 8th | Jean-Louis Ravelomanantsoa | Madagascar | 10.2 | 10.28 |

Five days after his victory in the 100m, Jim Hines would compete in the men’s 4x100m relay. After facing off against them in the individual event, Hines would team with Charlie Greene, Mel Pender and Ronnie Ray Smith, who held the 100m world record with Hines and Greene but hadn’t been picked to run in the individual 100m event in Mexico. This all-star team would finish second in their preliminary heat behind a Cuba team containing Hermes Ramírez, Juan Morales, Pablo Montes and Enrique Figuerola. Meanwhile, a Jamaican team featuring Lennox Miller on the anchor leg would win the second of three 4x100m heats, setting a new world record mark of 38.6 seconds. In the semi-finals, the USA would again finish second behind Cuba in one, while Jamaica would break the world record once more to win the second in a time of 38.3 seconds.

Heading into the final, Jamaica were the favourite to win their first 4x100m relay gold medal, with Cuba, East Germany and the United States close behind. In the final, Charlie Greene would give the USA the best start of anyone, but a poor handoff would allow East Germany to lead into the second leg. Greene would pass Mel Pender the baton with the USA in 4th place. Despite Pender closing the gap, Ronnie Ray Smith would still receive the baton with the USA out of the medals. However, a great leg from Smith would put the USA 3rd with Jim Hines on the anchor leg. A botched final handoff from East Germany would see them lose their lead to Cuba, but US anchor Jim Hines quickly closed the gap to Enrique Figuerola. Halfway down the home stretch, Hines would overtake Figuerola and win by two metres to win the men’s 4x100m gold medal for the United States while winning his second gold of the Games. He would also set his second world record of the Olympics, as Hines, Greene, Pender and Smith would run 38.2 seconds (automatically-timed: 38.24 seconds) to win relay gold. This world record would stand until the next Olympics when the United States quartet of Larry Black, Robert Taylor, Gerald Tinkler and Eddie Hart would run 38.2 seconds (automatic time: 38.19 seconds) to win in Munich.

After the Olympics

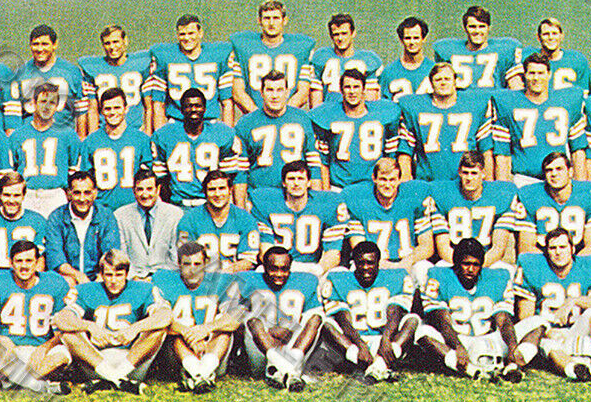

After his dual Olympic success, Jim Hines would turn his attentions to a different sport entirely: American football. In March 1968, Hines had declared himself eligible for the NFL/AFL draft. In the sixth round of the draft, AFL team Miami Dolphins would pick Hines, then a student of Texas Southern University. Hines would end up as the 193rd pick out of a total of 462 selections. In this selection, both the Dolphins and Hines would hope that the 1968 100m gold medallist ended up following the example of 1964 Olympic 100m gold medallist Bob Hayes. At the time, Hayes was the only man to win both an Olympic gold medal and a Super Bowl ring. However, due to his lack of football experience, Jim Hines would not make a single appearance for Miami during the 1968 AFL season, spending it instead in the Dolphins practice squad.

Nineteenth months after being drafted, Jim Hines would finally make his AFL debut against the Kansas City Chiefs on 19th October 1969. On his debut, Hines would appear as a wide receiver and wear the number 99. He would receive the ball once during this match, making one yard as the Dolphins lost 20-17 to the Chiefs. One week later, he would return one kick for 22 yards in a 24-6 Miami win over O.J. Simpson’s Buffalo Bills. In his third, his total involvement in the Dolphins 28-3 loss to the Bills was one 22-yard reception. The following week against the Houston Oilers (a 32-7 defeat), he would rush the ball once, making seven yards. If you think that these numbers do not make for impressive reading, then you would be right. In his first season playing American football, Jim Hines would play 9 matches for the Miami Dolphins, starting once. In total, Hines would return one kick, receive the ball three times, make a total of 30 yards (rushing and receiving combined), fumble the ball once and score zero touchdowns. He would also fail to score a single touchdown. He would even earn the unfortunate nickname ‘Oops’ as a reference to his lack of football skills.

After the 1969 season, the Miami Dolphins would trade Jim Hines to the Kansas City Chiefs for the 1970 NFL season, the first after the NFL/AFL merger. He would appear once for the Chiefs, the No. 88 failing to register any kind of statistic in his only official NFL match. After he was dropped at the end of this season, Jim Hines would give up American football. After his brief football career, Jim Hines, still aged 24, would return to the athletics circuit. However, he would never return to his previous level of notoriety. He would continue to compete on the athletics circuit on and off until 1984 but would never make another US Olympics squad.

Conclusion

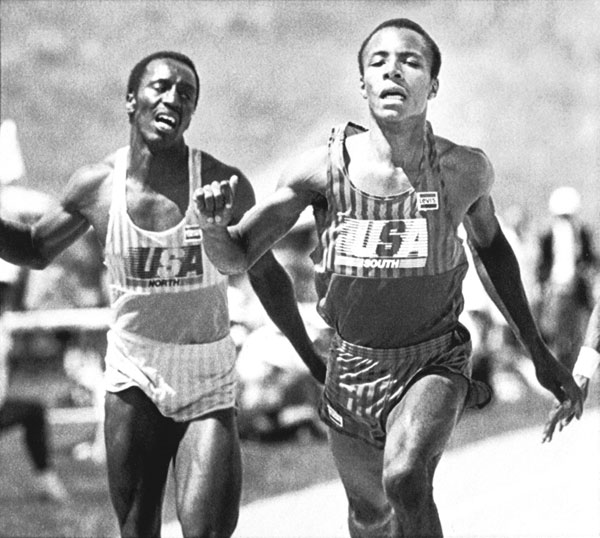

In late 1976, the world athletics governing body IAAF (International Amateur Athletic Federation) (now World Athletics) would announce that from 1st January 1977, automatic timing machines would become the primary way of measuring and recording the official times for race results. As part of this change, the IAAF would set the books straight regarding the men’s 100m world record. By this point, nine men had run the current hand-timed world record time of 9.9 seconds. Along with Jim Hines, Charlie Greene and Ronnie Ray Smith’s times from the 1968 US National Championships, Eddie Hart (1972), Rey Robinson (1972), Steve Williams (x4 1974-76), Silvio Leonard (1975), Harvey Glance (x2 1976) and Don Quarrie (1976) had all broken the 10-second barrier and could claim to be the world’s fastest man.

However, by consulting the automatic equivalents of these hand-timed 9.9-second runs, the IAAF would adjudge that only one of these nine men had broken the 10-second barrier and was the world record holder. That man was Jim Hines, with his Olympic gold-medal-winning run from Mexico City becoming the new and established world record with a time of 9.95 seconds. In fact, according to these automatic times, Hines had broken the world record, lost it and then broken it again in the space of three months. His 9.9 second-run from the US National Championships semi-finals, later calculated as 10.03, had broken Bob Hayes’s 10.06 world record set at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. The day before his 9.95 in the Olympic 100m final, Hines had lost the world record to Charlie Greene, who had won his Olympic quarter-final in an automatically-timed run of 10.02 seconds. However, Hines would reclaim the men’s world record with his now-famous run the following evening.

It would take 15 years for someone to break Jim Hines’ 100m world record time of 9.95 seconds. By mid-1983, two other men had run under 10 seconds but had failed to break Jim Hines’ world record. Cuban athlete Silvio Leonard, who had equalled the hand-timed world record of 9.9 seconds before the rules changed, had run 9.98 seconds in August 1977. Then, on 14th May 1983, a 21-year-old Carl Lewis had set a new personal best of 9.97, but just fifty days after this, Hines’ record would finally go.

On 3rd July 1983, at the US Olympic Festival in Colorado Springs, Colorado, 22-year-old Calvin Smith would become the fourth man to break ten seconds by winning the men’s 100m race in 9.93 seconds, two-hundredths of a second faster than Jim Hines’ world record. Like Hines’ world record time in Mexico City in 1968, Smith’s new world record was set at high altitude, an atmospheric effect that can improve athletic performance in sprint athletes. After losing the world record, Jim Hines would remain the fastest man in Olympic history until 1988, when Carl Lewis set a new world and Olympic record time of 9.92 to (legally) win his second consecutive Olympic 100m gold medal in Seoul.

Since Jim Hines’ 9.95 world record in October 1968, the 100m world record has been broken 11 times. Calvin Smith (9.93), Carl Lewis (9.92, 9.86), Leroy Burrell (9.90, 9.85), Donovan Bailey (9.84), Maurice Greene (9.79), Asafa Powell (9.77, 9.74), and Usain Bolt (9.72, 9.69, 9.58) have all had the honour of being the world’s fastest man. In addition, a total of 83 men have run faster than Jim Hines’ personal best over the past 50+ years. However, over fifty years later, just 0.37 seconds separates Hines’ world record from 1968 and the current world record time of 9.58, set by Usain Bolt in August 2009. On an athletics track, this equates to a distance of around 8 metres.

Before 14th October 1998, no man had ever broken the fabled 10-second barrier over 100m. On that night, Jim Hines would break through that barrier and write his name in sporting history. Over 50 years later, breaking the 10-second barrier remains a rite of passage for 100m runners, separating the good from the great. Jim Hines was the first to complete this rite of passage, changing athletics forever.